“Those without money can no longer breathe.”

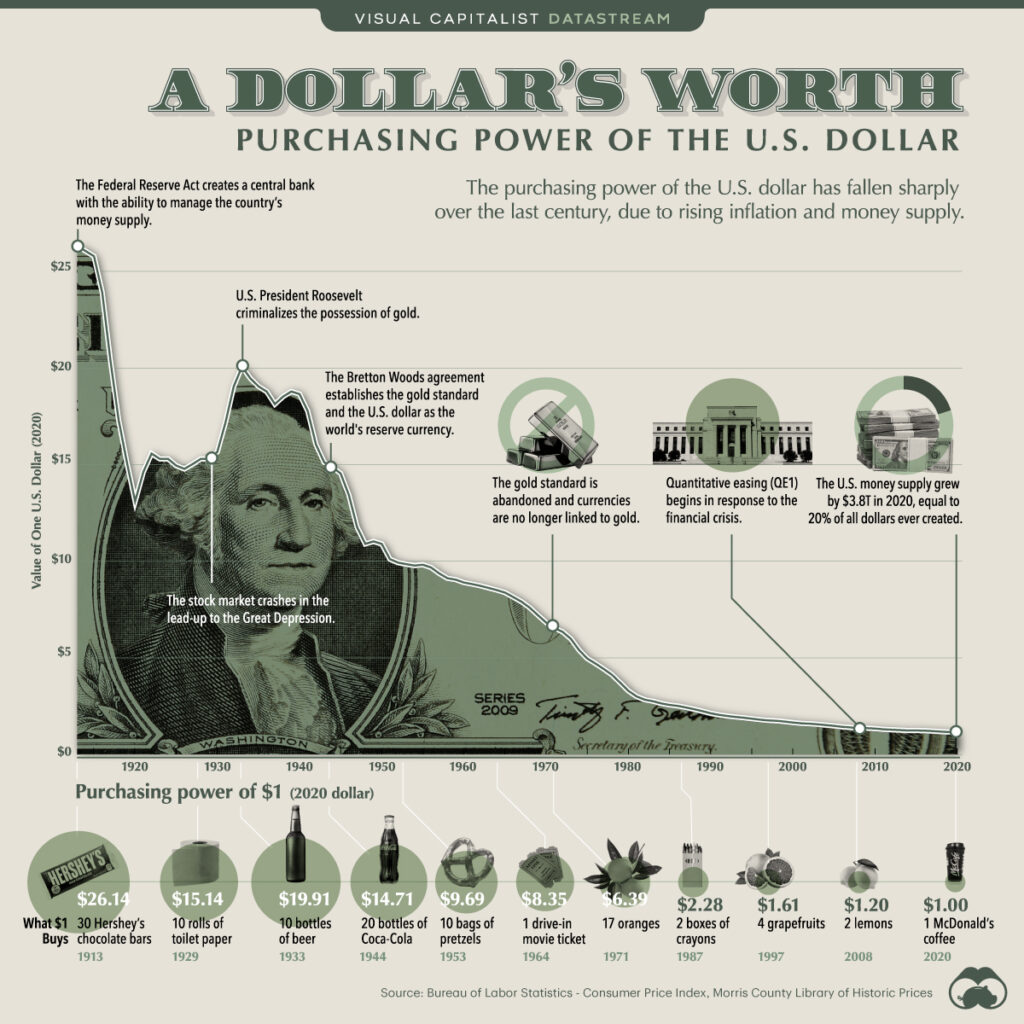

This phrase reflects an increasingly pressing reality in our society, where the purchasing power of money has eroded dramatically over time. Understanding this dynamic requires exploring the key historical events that have transformed the relationship between currencies and the goods and services they can buy.

The purchasing power of a currency, defined as the amount of goods and services that can be bought with one unit of that currency, has suffered a constant decline. A look at the U.S. dollar offers a clear example: what could be bought with $1 in 1913 would require $26.14 in 2020. This decline isn’t abstract; it translates into striking everyday examples:

- 1913: One dollar bought 30 Hershey’s chocolate bars.

- 1933: One dollar was equivalent to 10 bottles of beer.

- 1944: One dollar could get 20 bottles of Coca-Cola.

- 1964: One dollar paid for a drive-in movie ticket.

- 2020: One dollar barely covers a small coffee at McDonald’s.

From Gold to Paper

The history of money is marked by critical events that have accelerated this loss of value, many of which are related to gold. In 1933, during the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6102, which required citizens to surrender their gold to the government in exchange for dollars, consolidating state control over gold reserves. This marked a key step toward the centralization of the monetary system, followed by the Bretton Woods Agreements in 1944, which established the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, backed by gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce.

The turning point came in 1971, when President Richard Nixon eliminated the dollar’s convertibility to gold, in what became known as the “Nixon Shock.” This decision freed the financial system from the restrictions imposed by gold, allowing unlimited money printing. Since then, gold ceased to be the basis of the dollar, marking the beginning of an era dominated by fiat currencies.

In 1974, the U.S. Congress repealed the 1933 restrictions, allowing citizens to own gold again. However, by then, the monetary system had already changed radically: gold had lost its direct role as backing for the dollar, and the global economy operated under a fiat system based on trust in central banks.

These decisions have accelerated the loss of money’s purchasing power. The money supply in the United States went from $4.6 trillion in 2000 to $19.5 trillion in 2021, with a dramatic increase during the COVID-19 pandemic, when 20% of all dollars in circulation were created in 2020 alone. This explosive growth in the money supply has intensified inflation and further reduced the value of money in real terms.

In this new economic paradigm, traditional saving has become ineffective. Keeping money in cash or bank accounts means accepting a constant loss of purchasing power. To preserve real wealth, it’s crucial to invest in assets that outpace the inflation rate, such as real estate, stocks, or even gold itself, which, although displaced from the official monetary system, remains a historically recognized store of value.

The modern economy demands proactive financial action. Passivity not only guarantees losses but also aggravates long-term economic vulnerability. In a world where “those without money can no longer breathe,” investment isn’t just an option, but a necessity for financial survival.